I have a few upcoming conference talks and one of the themes I’m going to explore is the idea of ethics in cartography. The long held, and often repeated, ideal of what cartography constitutes is based on the notion that cartographers are a wholly objective breed who use clean and unequivocal data to tell the absolute truth through the map. This would be wonderful. It’s a fallacy. But that doesn’t mean we can’t work towards people making more truthful maps.

Pretty much every cartographer I know appreciates Mark Monmonier’s classic text ‘How to lie with maps’ which explains very clearly how maps can be used to mislead, or misinform for a variety of reasons, most of which are entirely innocent but which nevertheless often occur. It’s a staple of geography programmes, and embedded in the mindset of cartographers. Beyond that congregation, who else might have read it and brought those ideas to their seeing and reading of maps? It’s a two-way street and map-readers have a role to play. Of course, maps can also be made for extremely persuasive, propagandist, and nefarious purposes, and often deliberately. And if you’re not well versed in looking out for this type of map it’s likely hard to spot it. Maps are believable.

And just as I was ruminating, Greg Bensinger published an opinion piece in the New York Times today called The Maps that Steer us Wrong which prompted some more thinking. And so I thought I’d try and organise my thoughts here.

A few weeks ago I wrote a blog called Ethical Cartography that re-stated some common thoughts on how to pursue (or encourage) an ethically or morally defensive position when making maps. The simple ideas are not mine. They’ve been fashioned over decades by many different academic and practicing cartographers, and might be framed around the idea that cartographers ought to (or tend to) adhere to a checklist of due diligence, to ensure that they’ve covered off all the questions someone might ask of the map. Put simply, for every decision you make when making a map, ensure you have a justifiable answer, even if you made a deliberate decision to not do something on the map, still, make that a positive decision. If you put thought into every mark on the map then you should be in good shape, and adhering to that code means you can defend your map and its message.

That’s not to say someone else might not make a different map with equally justifiable decisions because, frankly, give the same data to ten cartographers and you’ll likely get ten different, yet equally ‘correct’ maps. But they might all look very different because every map is a compromise, and an opportunity to sell an idea through the visual medium of the map, that frames a particular angle you might take. Different maps often just tell different shades of the truth (someone should write a book about that).

Bensinger’s article opened with the line “Too many of our digital maps are sellouts.” and he went on to add his voice to the countless others over the past decades who have complained about maps that misinform in some way. He called out maps that use inappropriate projections that distort, or the compromises that have to be made to publish maps at much smaller scales than 1:1 while attempting to retain all the reality of their original scale. He suggests that the gap between reality and our digital worlds is becoming wider. I’d contend things have improved somewhat. The detail we have in our pockets these days is immeasurably more, and more accessible today than ever before. Are all the maps perfect? No, but they never have been.

He then pivots to explain how maps have always been made to show the world how map-makers have wanted to portray it. Presumably this includes all of the influences and powers that exerted how land, borders, and possessions were to be portrayed (rightly, or more often, wrongly). For it’s a very special type of cartographer who exists in their own vacuum, and who has carte blanche to make a map free of bias, external will, or without an angle to tease out. Bensinger also complains about the proliferation of Google Maps and its advertising, and of Redfin, and Zillow, and cellphone companies who all use maps with inherent bias to reflect what it is they want their map to do for them as organisations. The latter of which all too often suggest signal coverage that goes beyond reality, and which uses national scale maps that obfuscate local realty, yet upon which some then depend to assess signal at a local level. And guess what? A county-based average signal doesn’t necessarily cover that entire county uniformly. The map is by design, and by design it fudges reality to sell more contracts to people who believe that their coverage is better suited to their needs than another provider. This is no different to your decision over which is the best toothpaste, or washing detergent, or burger joint. Maps have always been used as advertising hoardings. Cellphone companies, and Google are not the first.

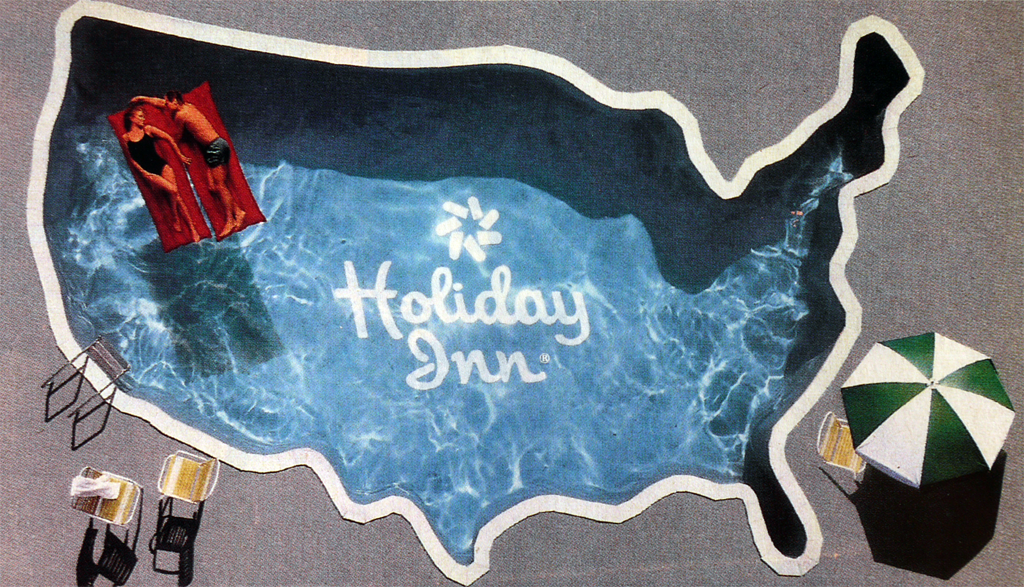

Maps are routinely used in advertising and they are normally used for one specific reason – to give the impression of just how far the phenomena being advertised has spread. There are numerous examples of maps that show us the spread of Starbucks or Walmart for instance and the map is really just a placeholder for the containment of thousands of points that we’re supposed to interpret as ‘they’re everywhere’. That may be true but sometimes advertisers use maps in far more inventive ways.

This 1985 advert for Holiday Inn gives us the impression of national coverage. The use of the map of the United States and the imprint of the logo on the pool’s lining gives us the clear message that you can find a Holiday Inn in all corners of the country. But the advert goes further. The pool is sun-lit and inviting. It’s clean and welcoming with the parasols and chairs. The relaxing, carefree couple give us a sense of how we might expect our stay to be.

People believe what they see. Maps are extremely good graphic devices to support a whole range of different messaging. That said – I’ve never seen one of these pools at a Holiday Inn so it’s a blatant lie.

The difficulty I have with Bensinger’s opinion piece is firstly that it offers little new to the debate, and simply propagates well worn tropes. Were once maps perfect, and free of misinformation? Were maps made by people with much higher morals and ethics than today? Were maps never used to advertise? Are maps now made by bad actors using bad data to deliberately tell bad stories? Is this because maps used to be made by experts but now are made by anyone? No to all of this. I’d suggest it’s the same as it ever was.

Some of the best maps in cartographic history were made (or commissioned) by non-cartographers. They were electrical engineers (Beck), nurses (Nightingale), social reformers (Booth), road and rail engineers (Cheysson), civil engineers (Minard), physicians (Snow) etc. Are these great maps any more or less great than Google Maps? Are they any more or less truthful? And for what purpose were they made because that’s the crucial component in any assessment of a map’s worth?

They were made to sell, whether it be a better route through a network, a better quality of life, a relaxing stay at a hotel chain, or a picture of the futility of war. Google Maps is made to sell. Remember, Google is an ad company, and selling ads is how they make money. The map is an advertising hoarding, albeit one that has extremely useful side-effects for everyday activities such as navigation. But ultimately, it’s just a very successful advertising hoarding that instead of being road-side, has found its way into your pocket. Google maps places you at the centre of your own personalised advertising hoarding to show you what is near. Companies pay for them to be shown. But as a curious map-reader that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t question what it displays and why.

And so yes, every map made then, or today, is a function as much of its maker, as of the data it is based on, as much it is the point of making the map in the first place. Some make maps according to strict organisational specifications. Do they get everything right? I doubt it. Some maps are made by individuals who wish to cast a light on particular patterns or issues. Are they always unequivocal? I doubt it. Some maps will promote one restaurant over another, or suggest one cellphone network is better than another, or position a boundary in one place for one set of readers, and another for another. Are they always correct for everyone? I doubt it. But to complain that maps should be always correct because cartographers should be held to a higher accountability is missing the point. The cartographers that I know do their best, and often in the face of constraints not of their making which maybe, just maybe affect the result. Cost, time, data quality, deadlines, the misplaced opinions, actions, and demands of others, and any number of other insults affect a map.

And because we can never 100% trust the map we are looking at, we must doubt, or bring a healthy skepticism, to it. Ask the questions of the map and why it exists, what it is designed to support, and how that message might be mediated by the design it takes. Why? Because map-makers are human, and to err is to be human. Couple that with the many complicated constructs we each operate within and it’s no wonder maps can be liars to some extent or another, of that Bensinger and I appear to agree.

And before someone wonders if my maps are free from such apparent tyranny, consider the fact that my maps are (mostly) made under my contract of employment. This will be the same for possibly 99% of anybody who makes a map. What, then, is the purpose of the maps I make, and how might the environment in which I work influence them? For me it’s simple. My intent is to sell the idea that better maps support a better truth, and by way of the map, a better, less incumbered mechanism for people to see an objective, truthful display of that information. I’m the same as the next cartographer trying to sell an idea, though circling back to the ethics in cartography that I’ve learnt and developed throughout my career I would hope I have integrity in that regard. But stating that is only part of the equation. My work has to stack up, and it’s only through time that I can build a portfolio that persuades people that they can trust my work. That trust has to be built.

But what does the company get in return for my work because that’s one context in which my work is conducted. My maps (and books for that matter) are all mechanisms to demonstrate that you can make terrific maps using the software, tools, data, and services provided by the company I work for. It would be ridiculous for me to make maps using the software of a competitor for instance. But I am fortunate that I do not work under restrictive demands with regard to the content I design and share. I can therefore contribute to the wider community of map-makers as part of the professional community of cartographers I belong to, and the application of the code of conduct I adhere to in my own map-making.

All maps are marketing something, be it a conservation message, or where your nearest Starbucks is. All maps provide the opportunity to share a great message. All maps are ads. Maybe the search shouldn’t be for more truthful maps (though making maps that are more truthful should be an ongoing aim), but for more worthwhile maps, and perhaps fewer, but more consequential maps.